From Trespass to Eviction: What Landlords Need to Know About Squatters

With rising vacancy rates and complex eviction laws, California landlords face growing challenges when unauthorized occupants take over properties.

Understanding how to prevent and respond to squatters can help protect your investment and avoid costly legal disputes.

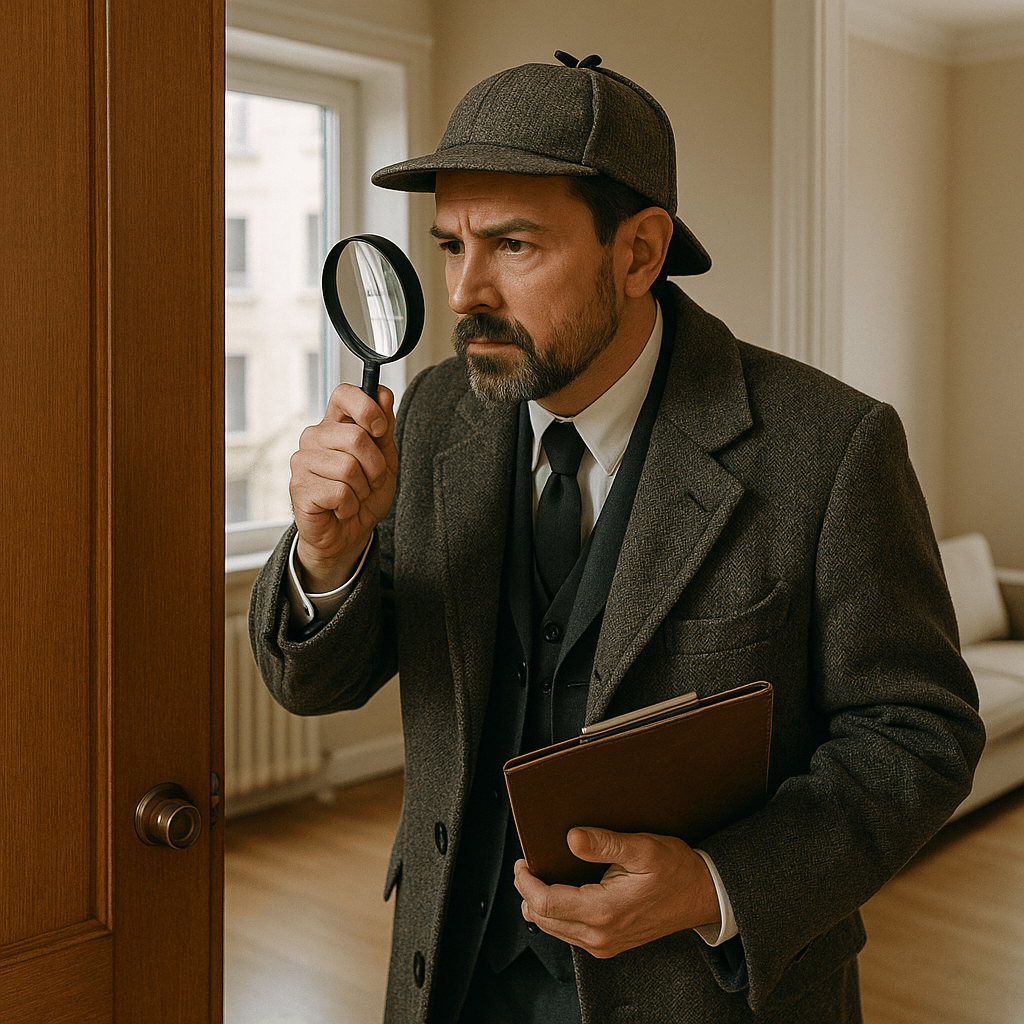

Tragically, it’s a scene we see too often: owners return to their vacant property only to discover that unfamiliar faces have forcibly entered, made themselves comfortable, and refuse to leave. Even worse, some individuals produce forged lease agreements or property deeds. These fraudulent documents—coupled with actions like setting up utilities in their name—can create a paper trail that makes it difficult for law enforcement to intervene.

Squatters wreak havoc for property owners and neighbors alike. They often inflict tens of thousands of dollars in damage to the properties they occupy, bringing down the value of nearby homes. Many squatters are also involved in other criminal activities, such as narcotics or theft. When squatters falsely claim a right to occupy the property, a lengthy legal battle may ensue, leaving owners unable to sell or rent it.

What Is Squatting, Anyway?

This is a broad term. We must delve deeper into the legal status of individuals occupying a property. Are they total strangers who have broken in? Has someone been allowed to stay but overstayed their welcome? Are they tenants—or has a tenancy been inadvertently created? Are they family members or caregivers who remain without the owner’s permission? Questions abound.

![]()

Trespassers

These are individuals who simply break into a property and brazenly take it over. They have no rental agreement (verbal or written) and have not paid rent. They are the type of people normally referred to as “squatters” and, notably, do not enjoy tenant protections such as “just cause” eviction requirements.

Licensees

These are individuals who have been allowed to stay for a time and refuse to leave when the owner asks them to vacate. The licensor—the owner—grants another person (the licensee) the right to use the property, but that right can be rescinded at any time. A common example: a son or daughter who hasn’t gotten their life together moves back in with their parents. The occupant enjoys the benefits of living in the home without paying rent, but the parents can later tell their child that the time is up and they must go.

Those Who Can Legitimately Argue They Are Tenants

Even without a formal lease, occupants can sometimes make a cogent argument that they’re entitled to remain. This may occur if rent money has exchanged hands, or if the owner knew someone was occupying the unit for an extended period and did nothing. Occupants might also claim there was a quid pro quo—that they were allowed to stay in exchange for work or another benefit. The optics are different in this case.

Bona Fide Tenants

When an occupant has a lease and pays rent, they are afforded tenant protections and must be removed through a formal eviction process. For example, a landlord gives a tenant a 60-day notice to vacate, but the tenant remains after the deadline. Or, after a master tenant vacates, the landlord gives written notice to a subtenant who still refuses to leave.

Identifying Squatters: Telltale Signs to Watch For

-

Someone moved into a vacant home, and no one saw any moving trucks

-

Numerous jugs or buckets of water are coming into the property (squatters rarely have running water)

-

The property’s “For Sale” or “For Rent” sign has been taken down

-

Candlelight or small fires inside or outside the home (many squatters lack utilities)

-

Trash is piling up in the yard or around the house

-

Personal items appear, like clothes hanging on a line

-

Constant foot traffic, often at all hours.• Signs of forced entry, such as broken windows, damaged doors, or tampered boarding

-

Unfamiliar cars are parked in the driveway or nearby

-

Mail is being delivered to a vacant property.

-

A sudden, unexplained spike in water or electricity usage

-

Makeshift alterations or repairs

Monitoring and Securing the Property

Owners and their agents need to be the eyes and ears of their property. To monitor for signs of squatting, owners can use both physical and technological methods—regular inspections, security systems, and communication with neighbors. Once discovered, documenting any suspicious activity is crucial to taking legal action.

At Bornstein Law, we often say that while technology is useful for screening tenants, it’s not a panacea—and the same applies to monitoring properties for squatters. There’s no substitute for old-fashioned vigilance.

A word of caution: do not take the law into your own hands. Squatters are often desperate, mentally unstable, under the influence, or involved in criminal activity. Confrontations can quickly escalate into dangerous situations. It’s better to observe from a safe distance and document the unauthorized stay rather than risk injury. Vigilantism can also lead to criminal charges if the owner initiates a physical altercation.

Our strong preference is to deter illegal inhabitants before they ever enter the property. Here in San Francisco, tenant advocates have even compiled public records to identify vacant properties and provide tips to would-be squatters. In response, we offer these strategies to “squat-proof” your property:

-

Fortify the property: Use high-grade locks purchased from a locksmith, and reinforce or secure windows.

-

Install video security systems: While Ring and Alexa devices are popular, other systems offer stronger cybersecurity and real-time monitoring.

-

Create the appearance of occupancy: Park a car in the driveway and use smart bulbs or timers to turn lights on and off automatically.

-

Coordinate with the post office: Ask USPS to remove any “vacant” designation from your mailbox, which can attract trespassers or burglars. Post “No Trespassing” signs under Penal Code §602.

-

Notify local law enforcement when a property will be vacant for an extended period.

-

Regularly inspect vacant units.

Keys, Locks, and Legal Considerations

Generally speaking, California frowns upon “self-help” eviction measures like changing locks. The owner must first determine the occupant’s legal status.

If the individual is a tenant or has a bona fide claim to tenancy or title: Do not change the locks. An illegal lockout can result in civil penalties, daily fines, and even criminal charges under California Penal Code §418.

If the individual entered unlawfully without permission, some owners are tempted to immediately change locks or board up the residence, but this “nuclear option” can expose them to liability if the occupant later claims a legal right to be there.

The owner’s legal footing is stronger when the squatter has occupied the property only briefly. After about 30 days, an occupant may transition from trespasser to someone who must be removed through formal civil eviction.

If police are called, it’s ultimately up to responding officers to determine whether the situation is criminal or civil. Reporting an active break-in via 911 increases the chances law enforcement will treat the intrusion as a criminal matter.

However, this approach is not appropriate if the individual is a subtenant, holdover tenant, or someone with established residency.

The 602 Letter

A 602 letter is a written notice a property owner (or their attorney) gives to someone unlawfully occupying or trespassing on property. It authorizes law enforcement to remove trespassers even when the owner is not present.

Its authority derives from California Penal Code §602, which defines various forms of trespassing. Under SB 602, property owners can now keep their 602 letters active for up to one year, extended from 30 days. If a property is permanently closed and posted as such, the authorization remains in effect for three years.

Key Elements of a 602 Letter

-

Property identification (address, unit, or parcel)

-

Statement of ownership• Notice that the person is not authorized to occupy the property•

-

Demand to vacate immediately

-

Reference to Penal Code §602• Signature of the owner or attorney

Forcible Detainer vs. Eviction

An eviction refers to the legal process to remove a tenant who has violated their lease—often for nonpayment of rent or another breach. The standard eviction lawsuit in California is called an unlawful detainer. A forcible detainer, however, is a broader term that includes situations where someone occupies your property without permission, even if they were never a tenant.

With Bornstein Law’s assistance, a Notice to Quit can be served to demand that trespassers vacate within a fixed period. If the squatter’s name is unknown, a fictitious name like John or Jane Doe can be used. If the occupants fail to respond within five days, we can seek a Default Judgment.

At trial, we must prove:

- The plaintiff is the owner of the property;

- The occupant lacks permission or consent to occupy it;

- The owner properly served a Notice to Quit;

- The occupants continued possession after notice expired; and

- The owner was deprived of possession. Once judgment is obtained, the Sheriff’s Department will return possession of the property to the owner.

Daily Value of the Property in Forcible Detainer

When a tenant or trespasser wrongfully holds over after their right to possession ends, the landlord may seek damages for each day of unlawful possession. If the court finds the occupant guilty of forcible detainer, the landlord is entitled to restitution and damages equal to the reasonable rental value during the unlawful period (the “per diem” value). (California Code of Civil Procedure §1174(b))

Unique Circumstances in Probate, Trust, and Inherited Properties

Settling an estate is already difficult, and the situation becomes even more challenging when the property is occupied by beneficiaries, relatives, or others who refuse to leave. When a property owner passes, it’s not uncommon for family members, friends, caregivers, or others to continue living in the estate home. Often, an adult child has lived there for years without paying rent.

When they refuse to leave, Bornstein Law can deliver the difficult but necessary message that it’s time to move on.

Family disputes often run deep, and emotions can cloud judgment. Our firm remains focused on the legal objective: effectuating a vacancy. The first step is to determine whether a landlord-tenant relationship existed with the deceased owner. If the occupant has no lease and pays no rent, they are not tenants and are not entitled to tenant protections, including “just cause” eviction laws.

Our office can send a letter informing the occupant that they must vacate. Often, hearing from an attorney prompts voluntary compliance. If not, the Personal Representative has the right to file a forcible detainer action.

Action items:

- Confirm the person is a squatter (not a tenant).

- File a 602 letter (notice to vacate).

- Contact law enforcement if applicable.

- Begin unlawful detainer proceedings if needed.

Of course, Bornstein Law can assist in every step along the way and help owners get peace of mind by reclaiming their property when they are held hostage.