An important legal case challenging Berkeley's application of its rent ordinance comes to a disappointing end

Regulators now have the discretion to decide if they are regulated themselves

![]()

In an earlier article, we said that even if efforts to repeal or amend Costa-Hawkins fail in the statehouse or at the ballot box, the longstanding law limiting local governments to impose their own rent regulations can still be subject to interpretation in the courts. The most recent case on our radar was NCR Properties, LLC v. City of Berkeley.

Background

After landlords purchased two derelict single-family homes that were once used as rooming houses and extensively rehabilitated them, they were granted new certificates of occupancy. It stands to reason, then, that they were exempt from Berkeley's Rent Stabilization and Eviction Ordinance, right?

Not all of the units, according to Berkeley's Rent Stabilization Board. Since four units were rented for residential use before the new certificates of occupancy were issued, the Board reasoned, those units were merely converted from one form of residential use to another and hence, were not new construction.Only two units - an attic unit in one building and a basement unit in the other were exempt under Costa-Hawkins.

The judiciary agreed

Litigation followed and when the trial court sided with Berkeley, the landlords appealed. In a 3-0 vote, the Court of Appeal upheld the lower court's decision and most recently, the California Supreme Court declined to review the case.

Our thoughts, for what it's worth

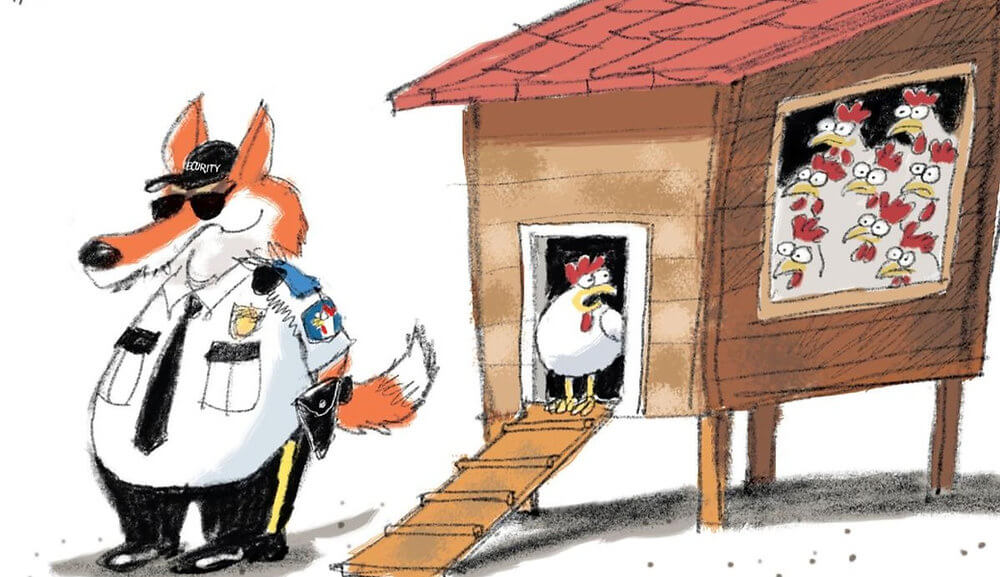

In this case, the courts have essentially allowed Berkeley to circumvent Costa-Hawkins and send a signal to local governments that regulators have the discretion to decide whether Costa-Hawkins applies or not. This is like the fox guarding the henhouse - local officials can decide whether state law designed to limit their power is applicable in a case at hand.

When a property owner endeavors to evict a tenant on the theory of substantial rehabilitation, we have always had to qualify the term "substantial." Rest assured, it is not a fresh coat of paint or sanding a hardwood floor. Now, must we ask, does gutting the place lead to new housing stock? This decision sets a dangerous precedent. Time will tell how this plays out and whether this logic is spread to other Bay Area locales.

In a more abstract way, we think that this will only aggravate California's housing shortage because investors are less incentivized to make improvements in the state's aging housing stock.

Whenever no-fault evictions are contemplated, it is imperative to consult Bornstein Law, but now it got even more muddled.